Educational Consultant –

Specializing in Reading & Writing

Providing professional development for educators

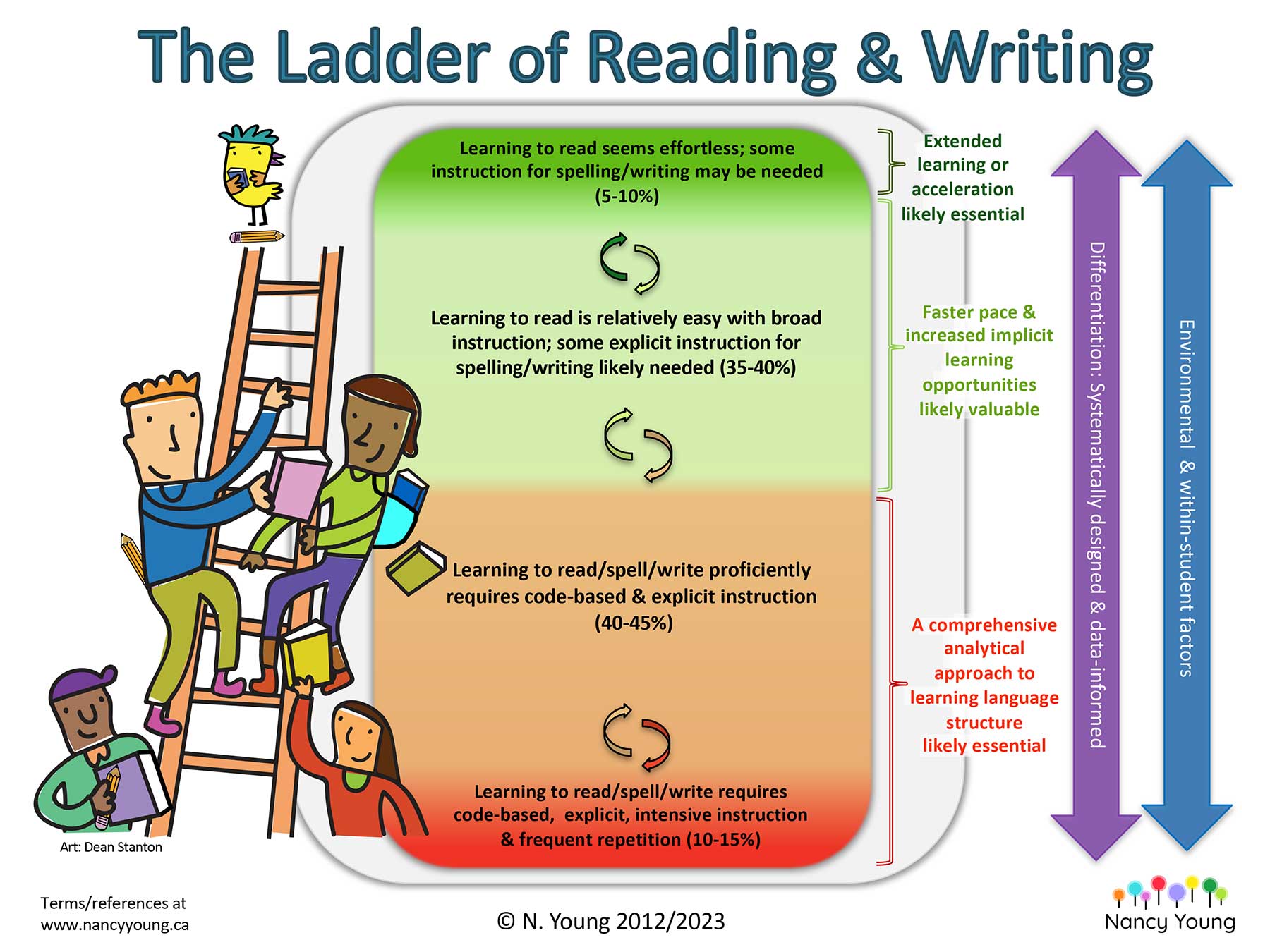

“EVERY STUDENT DESERVES CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION AND SUPPORT THAT IS DIFFERENTIATED FOR THEIR INTELLECTUAL ABILITY AND ACADEMIC READINESS. ALL INSTRUCTION SHOULD RECOGNIZE INDIVIDUAL STRENGTHS, INTERESTS, AND VARYING NEEDS, AND BE PROVIDED IN WAYS THAT ARE BOTH EFFECTIVE AND FUN!”

“EVERY STUDENT DESERVES CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION AND SUPPORT THAT IS DIFFERENTIATED FOR THEIR INTELLECTUAL ABILITY AND ACADEMIC READINESS. ALL INSTRUCTION SHOULD RECOGNIZE INDIVIDUAL STRENGTHS, INTERESTS, AND VARYING NEEDS, AND BE PROVIDED IN WAYS THAT ARE BOTH EFFECTIVE AND FUN!”

The eagerly awaited book

co-edited by Nancy Young, Ed. D.

and Jan Hasbrouck, Ph.D.

Climbing THE LADDER OF READING & WRITING

Meeting the Needs of ALL Learners

The Infographic:

The Ladder of Reading & Writing

Sign Up for my newsletter

* We do not sell or distribute your personal information.